It’s May 6th around 5 p.m. and it’s my very first bike ride of the season. Usually, I put rubber to pavement much earlier in the season, but it’s been a very busy spring for me. I cruise down my street in north Leaside, say hi to a few neighbours and head through the stone entrance to Serena Gundy Park. I often think of the names of parks and other natural landscapes around our city and how they are not recognized by their Indigenous names, rather they are known by names given by settlers who ‘discovered’ the area or settlers who owned the land and then donated it to the city to be used as parkland. A noble cause, but these names mask 13,000 years of Indigenous history in the city we know as Toronto, properly pronounced Tkaranto – a Mohawk word that means where the logs gather. So, for the sake of this article I will refer to the Don as it was meant to be called: Wonsoctanach.

Wonscotanach is an Anishinaabe word meaning burning bright light. It is believed that the river may have been given this name because of the fire-lit torch fishing that would have taken place here, beside and a little bit north of Leaside in the summer evenings many years ago. The name Don was given to the river by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe in 1793 because it reminded him of the River Don in Yorkshire, England.

This beautiful valley that meanders gracefully along the east side of our neighbourhood has been a point of contention in the history of our city’s agreed upon boundaries. The problematic Toronto purchase was drawn up in 1787, and the Mississaugas, believing that it was a rental of land and not a surrender, drew the city’s east boundary at the river. Since it was entered into a negotiation, the land was now vulnerable to challenges. It wasn’t long before that eastern boundary was challenged, pushed farther east, and the city acquired more Indigenous lands.

Plant life has purpose

To look at the land through an Indigenous lens is not to see plants and weeds (i.e., valuable vs. invaluable). It is, rather, to see all plant life as having purpose – as medicines and foods. Women are the keepers of these medicines and knowledge; plant life is known as Grandmother (Nokmis in Anishinaabe) – giving what settlers considered inanimate life an animate and loving relation. Rocks are called Grandfather (Mishomis in Anishinaabe) because the rocks are the oldest; second oldest to these is our earth’s beautiful and abundant plant life.

As I roll down the steep hill, I don’t get far before I’m off my bike and walking so I can look closely at all the ripe green medicines popping up out of the ground all along the trail. There are tiny maples dotted along each side of the steep concrete trail. Maples have been an important part of local Indigenous technologies. It was the Indigenous peoples who taught the settlers how to tap trees to extract the rich syrup – a skill which enabled many settlers to survive.

When I get to the bottom of the trail, I can see the stinging nettle’s dark green and jagged edged leaves all along the edge of the forest. This ancient medicine is native to Europe and most likely made its way here on ships; it now thrives in our ravines. It is very high in vitamins A, C, calcium and iron. I harvest nettle in mid-May, hang it outside my front door to dry and make it into tea, sipped hot or cold throughout the year.

Cedar grows in abundance throughout the Wonscotanach valley and in many of our own front and backyards. It is one of the four sacred medicines and it represents protection. It makes an incredible tea that is very high in vitamin C.

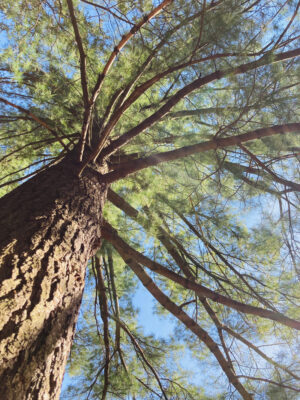

Next, I come upon four huge and magnificent white pine trees. The white pine is sacred to the Haudenosaunee Nation. It was under a white pine (the tree of peace) that the original five nations buried their weapons of war, thus becoming one under the Great Law of Peace. This was the inspiration for the American Constitution. If you pull off a bundle of needles you will notice they grow in fives to represent the original League of Five Nations: the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Onondaga, the Seneca and the Cayuga.

I continue on my bike ride, past the Science Centre, over the train track bridge, under the Leaside bridge and roll south. All along the west side of the trail you can witness the matrix of wild grape vines – they creep up trees and around lamp posts all over our city, and the grapes are incredibly tasty when picked in late summer. They are native to North America and they teach one of the Seven Grandfather Teachings: Love. The food forest is not just here for us to take from – rather, the plants and medicines teach us powerful lessons. Observing how grape vines carefully and meaningfully wrap themselves around trees, posts, or electrical towers reminds the people of the importance of embrace, support and love.

I get as far as Queen St., turn my bike around and head north again, towards Leaside. As I scan the vast mowed grassy areas of Seaton Park breezing fast under my wheels, I take note of how the lawns are almost equally plantain as they are grass. Plantain is native to North America and if you are ever stung by a bee, you can reach down, pick a few leaves and chew them up. Then take the chewed-up leaves and use them as a poultice over the sting to extract the venom.

And finally, I have to point out the ever so dominant garlic mustard. It was brought here from Europe in the 1800s to be cultivated as a food. Before too long, it took over and has become an aggressive invasive species taking over forest floors, our lawns and the edges of parking lots all over our city. It escaped the agricultural boundaries for which it was intended, has taken over natural habitats and threatened native species. It is not of value to native wildlife; rather it takes up space and displaces native flowers such as trilliums. It also threatens the very existence of other native plants such as American Ginseng and wood aster. You can pick it – and I encourage you to, as it does make a very good pesto. But it always comes back, the seeds spreading far, deep and always acquiring more land meant for native species.

I guess plants are not that much different from people and, therefore, garlic mustard is one with colonialism.