Leaside is well-known for its shopping, its restaurants, its leafy streets, its 72 storage facilities … and its history of ski jumping.

Yes, neighbours, Leaside was once THE hub of ski jumping in Toronto.

In the 1930s, ski jumping was all the rage. With Toronto jumpers travelling to Ottawa, Peterborough, Midland, and beyond, to get their fix, the Toronto Ski Club (TSC) felt it was lagging behind other clubs and decided to try to catch up by designing its own ski jump.

TSC chose a spot at the western edge of the Don Valley. The site, at the very eastern end of Wicksteed, led down to what is now, approximately, the back of the Ontario Science Centre.

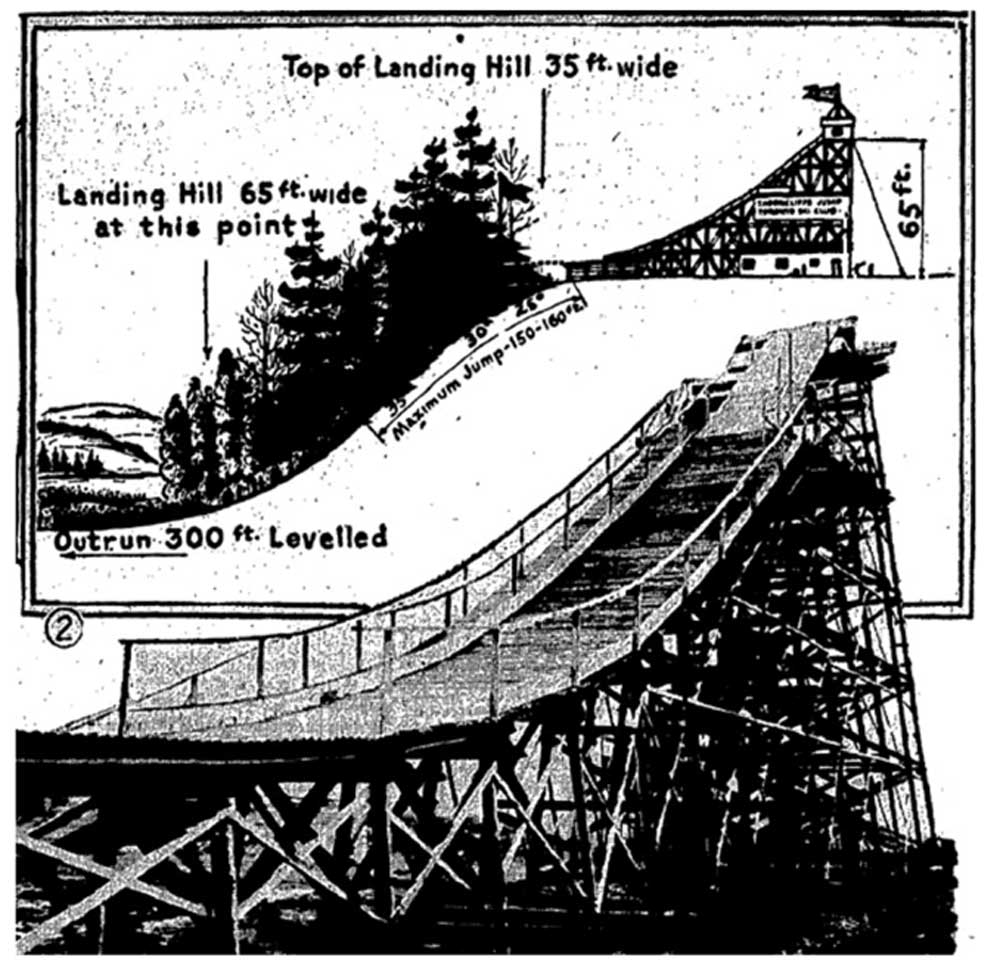

Designed by TSC’s Fred Hall, the jump was built in January 1934 for $2,500. The next year the Globe and Mail described the ski jump, which soared 65 feet, as “slightly lower than the height of the Royal York Hotel.”

But there was one tiny issue. Toronto’s balmy winter of 1934 meant there wasn’t enough snow to cover the jump. The solution? One hundred tons of ice were scraped off the surface of the rink at the University of Toronto’s Varsity Arena and transported to the site.

After testing the jump and making the necessary alterations to ensure jumpers didn’t end up plummeting into the Don, club officials felt it was ready for its first competition, the provincial championships, on the weekend of February 10th.

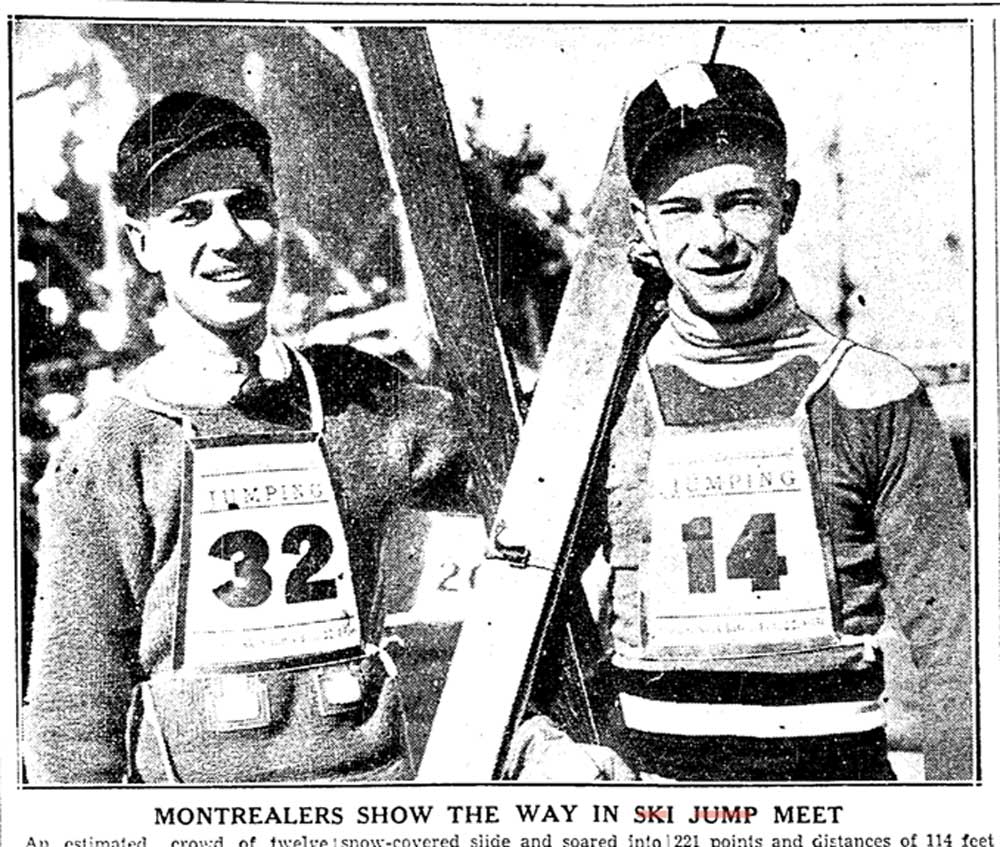

Canadian Pacific ran a special train to the site from its North Toronto station and others surged there by car and on foot. An estimated 10,000 spectators were in attendance for the championship. The main competition was won by Ottawa skier Jack Landry, who had two jumps over 120 feet, while second place went to 14-year-old Montreal skier Percival Christian “Punch” Bott, who had two jumps of 115 feet.

The Thorncliffe Jump hosted the city championships the following weekend with Celius Skavaas winning the event.

After a successful 1934 season of competitions, the site was ready for an even bigger event.

January 26th, 1935 was a monumental day for the TSC and the city itself. Hosting the international ski jump championships that day with competitors from 50 countries, Toronto kicked off the tournament with a grand welcome of the skiers at Union Station, followed by a parade up Bay Street.

H.P. Douglas, the editor of the Canadian Ski Year Book, who attended the event, described the parade: “Headed by a police escort and a military kiltie band, some hundred skiers in ski clothes, with skis on shoulders, marched from the Union Station to the City Hall to be received on the steps by Mayor Simpson and his Civic Council.” He added: “It was amazing to we (sic) Montrealers, used to the apathetic attitude of the Montreal public, to see this great outburst of enthusiasm.”

The Toronto Daily Star commented that skiers were met by “the cheers of office crowds and reams of ticker tape.”

Douglas also commented on the event itself, noting that “the roads (to the jump) were crowded with cars, and special trains brought their quotas, and from the judges’ stand it was an inspiring sight to see this huge gathering of spectators.”

The Dominion Championships, held in February of the same year, attracted some 10,000 spectators.

Several smaller competitions took place over the next number of years with the final competition in 1941. The event was organized by the Canadian Amateur Ski Association and the Norwegian Air Force, which had a training camp in Toronto during the war, and featured a spectacular opening ceremony with bugle players and a flyby from the Norwegian Air Force.

This competition wrapped up the existence of the Thorncliffe Ski Jump. With more reliable winter weather north of the city, skiers favoured alternative jumps, and the jump was dismantled later that year.

Leaside is now home to two ice rinks, a curling rink, a swimming pool, and several baseball diamonds.

But in my books, a ski jump ranks so much higher (horrible pun intended).